I don’t know how it snuck up on me, but somewhere in the preparations for Field Day recently, I realized that it’s my Fortieth year as an Amateur Radio Operator.

There is no guarantee that it would be a life-long hobby, but in most cases it usually ends up being that way. Once you’re in, it’s easier to stay in than to let it lapse and start from scratch again. I’ve stayed licensed through dry spells where I have had no activity at all to times when I was very involved with the hobby. I always seem to be interested enough to follow what is going on, the politics and the technology of the hobby, both of which have changed a lot – and not all for the better – since 1969.

I really don’t remember when or how I got interested in Ham Radio. Somewhere about 5th-6th grade, I found a book in the library on electronics and built a crystal radio. I remember my father taking me to Buffalo to an area on Main Street that had several raqdio parts stores and we went from one to another with our list of parts. Little did I know that I would one day work in one of those stores.

I really don’t remember when or how I got interested in Ham Radio. Somewhere about 5th-6th grade, I found a book in the library on electronics and built a crystal radio. I remember my father taking me to Buffalo to an area on Main Street that had several raqdio parts stores and we went from one to another with our list of parts. Little did I know that I would one day work in one of those stores.

My interest in electronics continued until I was in High School, where I found two classmates had their Ham licenses. Doug Zastrow and Steve Llewellyn. I don’t remember Doug’s callsign and have lost touch with him, Steve was WB2OYE and was a very proficient CW operator and active in traffic nets sending messages across the country. Steve, unfortunately, passed away just before graduation.

We tried to start a Ham Radio club in school and even put together a station. We had the callsign WB2EET for a while. Several of us were studying the code and theory for the Novice exams, but none of us ever got very far. There were just too many other distractions in High School, from sports, to girlfriends, to drama club, etc. Eventually, the club fizzled out.

One spring, I noticed an ad in the local paper for Ham Radio classes. The local club was holding a course at the CD Building and it was open to anyone. I started attending. I was pretty confident that I could handle the theory and rules and regulations, as I had already been studying them from the school club. The code was the hurdle for most people. I had struggled with Morse Code all along and just couldn’t seem to get the hang of it. But I went in with an open mind and resigned myself to starting from scratch at the beginning.

A funny thing happened. It was easy. Of course, the first few letters were simple, I already knew the whole alphabet. But by starting out at the beginning with the slight advantage of already having been exposed to the code, I stayed ahead of the whole course. It became an easy practice session and as the class progressed along to the next set of letters each week, I was already comfortably copying them. Code became easy for me and I never looked back.

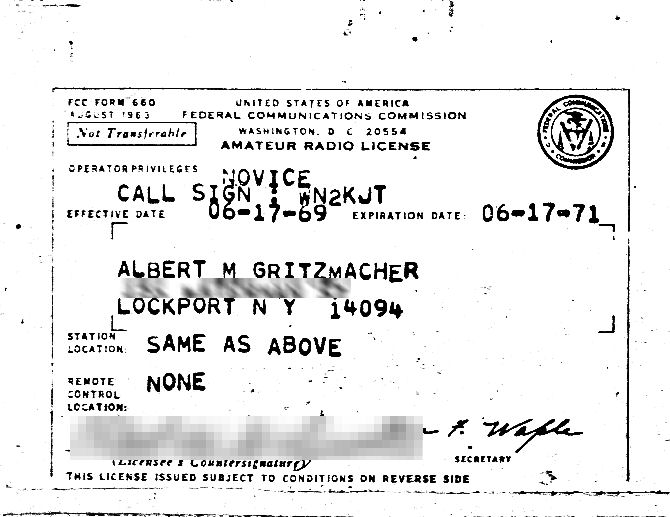

It was a good thing too. At that time there was only one entry point into Ham Radio, the Novice license. You could take the test from two licensed Hams, and they applied for and administered ours at the CD Building. It gave you limited privileges on only three Ham bands – 80, 40 and 15 meters – and only 75 watts of power. Furthermore, your transmitter had to be crystal controlled. That meant you were stuck to one frequency at a time. You had to buy a crystal – a quartz resonant piece that plugged into your transmitter – for each frequency you used.

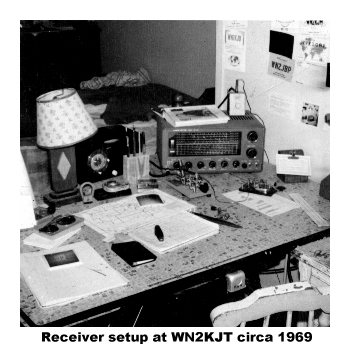

I had bought a receiver from my classmate Steve well before I took the class at the CD Building. It was a good way to practice my code and I also had great fun listening to all sorts of things. It was a Lafayette HE-30, a tube type general coverage short wave receiver, but it had good bandspread dials calibrated for all the Ham bands. People today don’t even know what bandspread means.

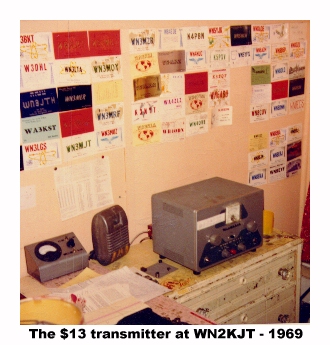

Once I had a license, I needed a transmitter. A friend of mine, Jim Chapman, who had been in the same club at High School and in fact had been a cohort all along through crystal sets and shortwave listening, had bought a transmitter at one of the local club auctions. Every winter, the hams in Lockport put on an auction where hams from all around brought equipment they wanted to sell. He had bought a Heathkit HW-35 transmitter. It worked and he got a good deal on it. The only problem with it was, the original transformer in it had failed. To make it work again, someone had wired up two transformers through a cable and rewired the accessory jack on the back of the case to plug them in. The two transformers were wrapped in duct tape and sat on the floor. A line cord with a inline switch turned it on and off. He paid the whopping price of $13 for it, even though he didn’t have his license.

I don’t think Jim ever did get a Ham ticket. Shortly after I got mine, he sold me the Heathkit for what he paid for it. The transmitter worked okay. It had a 6146 tube and those are nearly indestructable. The transmitter sat on a small dresser next to my table and the transformers sat on the floor. My Father always said he could hear the Morse code through the floor as the hum of the transformers changed.

I got on the air immediately. My Father helped me put up an antenna in the back yard. Actually, I had the antenna for the receiver for some time, but I rerouted the coax to my new shack in the attic. We didn’t know that the way we laid out the antenna, it wasn’t supposed to work. It just did anyway and I made lots of contacts with it. My first attempts at a QSO were comical. I think the first time someone answered me, I got so flustered that I couldn’t respond. But I kept at it and made contacts. My code speed got faster and faster. I eventually got to know many of the other novices who had crystals near the frequencies I had. When you are stuck on a handful of frequencies, you hear the same people over and over. You also learn to listen around you a bit in case someone has a crystal just a bit off your frequency. Our receivers were wide enough that it was easy to do.

In a way, this was the golden years for me and Ham Radio. It never got better than the thrill of getting someone to answer you with such basic equipment. Every day was another day of changing something to make it work better. New antennas. Tweaking equipment. Adding a filter here, rewiring an audio circuit there. Later years brought better equipment, but never more fun.